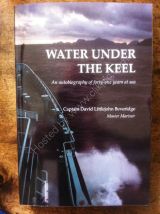

Water Under The Keel - The Book

WATER UNDER THE KEEL An autobiography of forty-one years at sea

Captain David Littlejohn Beveridge Master Mariner

Captain David Littlejohn Beveridge Master Mariner

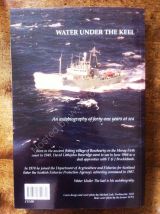

Water Under the Keel, a work encompassing a range of themes, are the memoirs of Captain David Beveridge.

Like the master mariner he is, David guides the reader through the varied waters of a man’s life-journey, through the tranquillity, squalls and tempests of domestic, social and political change; not least of these is the development (or regression) of Scotland’s fishing, from staple industry to endangered activity; coincident, or otherwise, with Britain’s closer relationship with Europe.

There’s also much of a spiritual nature, as well as travel writing from far and near.

Born in the ancient fishing village of Rosehearty on the Moray Firth in 1949, his family were economic refugees to London in the early fifties. David evokes the sights and smells of time and place, accompanying the reader through a house which was built for the sole purpose of yielding every minute particle of dust and dirt to the therapeutic power of Sunlight Soap, Mansion house polish and bleach.

From home births and rugs made from rags, the narrative takes us via locations as diverse as East Berlin and Mozambique, to the space-age marine computer systems of the 21st-century. Leaving the tenements and middens of post-war Partick, we travel through Aden and New Orleans, in the company of officers good and bad, Government Ministers, deckhands and EU Commissioners.

After signing on as Apprentice Ship’s Officer with T&J Brocklebanks in 1966, he progresses through the ranks, becoming a Captain in Scottish Fisheries in 1987. In addition to an evident work ethic, there also emerges a clear and articulate morality: when asked at a job interview with the Department of Agriculture and Fisheries for Scotland, for his views on fishery protection, he observes that it seemed axiomatic to me that if the law was to mean anything it had to be enforced. Not only that, it appeared to me that if a country took itself seriously, there was a clear connection between its sovereignty and its determination to protect its fishing rights. I said that we had our own law, our own Church and a long history of self-determination, so we should also see to our own seas.

A native of Buchan by birth, David’s roots lie in the fishing communities of north-east Scotland, and in the constants, not uncommon in that part of the country, of fishing and faith. His sometimes contradictory relationship with his father appears significant in his own development. (Never marry a Catholic, son. The son does just that). The narrative follows the trajectory from child’s view of his dad as hero, to flawed object of adolescent criticism, to ordinary guy with whom his son enjoys a mature and mutually-respectful relationship, culminating in the old man’s time on the Vigilant, of which David is now Captain. The reader shares in David’s pride as his dad (sometime Chief Marine Engineer, and ever a practical man) steps into the breach to organise the crew’s handling of seized illegal fishing gear.

The long voyages function as a metaphor for humanity’s often lonely search for spiritual fulfilment. An enquiring and reflective mind is stimulated by shore leave, observing an elephant procession in a Buddhist festival in Ceylon, and pondering colonial swimming clubs off-limits to locals. A young man at anchor in Suez Bay is witness to rockets and tracer bullets as the Six-Day War breaks out. The reader partakes of the spiritual emptiness in Bangkok strip clubs as morality, Presbyterian-influenced but open-minded, is exposed to the libertine behaviour of seamen ashore, leading to a crisis of values. Those who believe that God works through apparent coincidences will find much to recognise, notably in the crossings of David’s path with that of Tom Malone, Chaplain of the Port of Houston, Texas, and his faith becomes as constant as the Pole star.

It’s a faith that is tested to the limits as the baby daughter of David and his wife Patsy dies only three days after her birth, and the reader cannot fail to empathise with the crying in the wilderness that ensues. The qualities of both love and strength are apparent as the bereaved parents, orphans of their child, subsequently sire a family of eight. A sense emerges of a marriage which symbolises the union of a number of traditions: the seafarer and the homemaker; the Protestant, east-facing fishing folk of the Moray Firth, matched with the Scots-Irish Catholicism of Patsy’s native Lanarkshire.

David’s burgeoning family responsibilities lead to his leaving the long deep-sea voyages on large ships for the shorter patrols of Scottish Fisheries Protection Agency patrol vessels. Shorter, but one suspects more intense, as the duties of marine policeman are added to those of sea captain. We share in a number of emergency rescues described by the actual reports written at the time. All of this during times for the fishing industry which could euphemistically be described as “interesting”, and there are some forthright observations on related political aspects and regulation. However, his professional duties afford him the rare privilege of exploring Scotland by both land and sea, and there’s a true sense of happiness here.

The language although not overly technical, is sufficient to retain a nautical ambience, as well as a flavour of both Doric and Glaswegian, and there’s an immediacy to the descriptions. Your stomach retches at the demented violence of the night-time storm west of the Hebrides, and a night at anchor when the anchor cables stretched like bow strings, disappearing into the spray and thick glaur. You can feel the shutters come down over the Soviet officer’s eyes as he is presented with a Russian Bible. You can taste the spices, kebab shops, hookahs giving off the aroma of Turkish tobacco, heavy thick coffee and ten thousand things besides… in Jeddah’s Souk, and there’s a striking absence of bitterness at David’s realisation that his invention of a davit for launching and recovering boats safely at sea (a device now widely used on ships) will go uncredited. God knows the true identity of its inventor; and that, one senses, is enough for Captain Beveridge.

Dominic Brown

Like the master mariner he is, David guides the reader through the varied waters of a man’s life-journey, through the tranquillity, squalls and tempests of domestic, social and political change; not least of these is the development (or regression) of Scotland’s fishing, from staple industry to endangered activity; coincident, or otherwise, with Britain’s closer relationship with Europe.

There’s also much of a spiritual nature, as well as travel writing from far and near.

Born in the ancient fishing village of Rosehearty on the Moray Firth in 1949, his family were economic refugees to London in the early fifties. David evokes the sights and smells of time and place, accompanying the reader through a house which was built for the sole purpose of yielding every minute particle of dust and dirt to the therapeutic power of Sunlight Soap, Mansion house polish and bleach.

From home births and rugs made from rags, the narrative takes us via locations as diverse as East Berlin and Mozambique, to the space-age marine computer systems of the 21st-century. Leaving the tenements and middens of post-war Partick, we travel through Aden and New Orleans, in the company of officers good and bad, Government Ministers, deckhands and EU Commissioners.

After signing on as Apprentice Ship’s Officer with T&J Brocklebanks in 1966, he progresses through the ranks, becoming a Captain in Scottish Fisheries in 1987. In addition to an evident work ethic, there also emerges a clear and articulate morality: when asked at a job interview with the Department of Agriculture and Fisheries for Scotland, for his views on fishery protection, he observes that it seemed axiomatic to me that if the law was to mean anything it had to be enforced. Not only that, it appeared to me that if a country took itself seriously, there was a clear connection between its sovereignty and its determination to protect its fishing rights. I said that we had our own law, our own Church and a long history of self-determination, so we should also see to our own seas.

A native of Buchan by birth, David’s roots lie in the fishing communities of north-east Scotland, and in the constants, not uncommon in that part of the country, of fishing and faith. His sometimes contradictory relationship with his father appears significant in his own development. (Never marry a Catholic, son. The son does just that). The narrative follows the trajectory from child’s view of his dad as hero, to flawed object of adolescent criticism, to ordinary guy with whom his son enjoys a mature and mutually-respectful relationship, culminating in the old man’s time on the Vigilant, of which David is now Captain. The reader shares in David’s pride as his dad (sometime Chief Marine Engineer, and ever a practical man) steps into the breach to organise the crew’s handling of seized illegal fishing gear.

The long voyages function as a metaphor for humanity’s often lonely search for spiritual fulfilment. An enquiring and reflective mind is stimulated by shore leave, observing an elephant procession in a Buddhist festival in Ceylon, and pondering colonial swimming clubs off-limits to locals. A young man at anchor in Suez Bay is witness to rockets and tracer bullets as the Six-Day War breaks out. The reader partakes of the spiritual emptiness in Bangkok strip clubs as morality, Presbyterian-influenced but open-minded, is exposed to the libertine behaviour of seamen ashore, leading to a crisis of values. Those who believe that God works through apparent coincidences will find much to recognise, notably in the crossings of David’s path with that of Tom Malone, Chaplain of the Port of Houston, Texas, and his faith becomes as constant as the Pole star.

It’s a faith that is tested to the limits as the baby daughter of David and his wife Patsy dies only three days after her birth, and the reader cannot fail to empathise with the crying in the wilderness that ensues. The qualities of both love and strength are apparent as the bereaved parents, orphans of their child, subsequently sire a family of eight. A sense emerges of a marriage which symbolises the union of a number of traditions: the seafarer and the homemaker; the Protestant, east-facing fishing folk of the Moray Firth, matched with the Scots-Irish Catholicism of Patsy’s native Lanarkshire.

David’s burgeoning family responsibilities lead to his leaving the long deep-sea voyages on large ships for the shorter patrols of Scottish Fisheries Protection Agency patrol vessels. Shorter, but one suspects more intense, as the duties of marine policeman are added to those of sea captain. We share in a number of emergency rescues described by the actual reports written at the time. All of this during times for the fishing industry which could euphemistically be described as “interesting”, and there are some forthright observations on related political aspects and regulation. However, his professional duties afford him the rare privilege of exploring Scotland by both land and sea, and there’s a true sense of happiness here.

The language although not overly technical, is sufficient to retain a nautical ambience, as well as a flavour of both Doric and Glaswegian, and there’s an immediacy to the descriptions. Your stomach retches at the demented violence of the night-time storm west of the Hebrides, and a night at anchor when the anchor cables stretched like bow strings, disappearing into the spray and thick glaur. You can feel the shutters come down over the Soviet officer’s eyes as he is presented with a Russian Bible. You can taste the spices, kebab shops, hookahs giving off the aroma of Turkish tobacco, heavy thick coffee and ten thousand things besides… in Jeddah’s Souk, and there’s a striking absence of bitterness at David’s realisation that his invention of a davit for launching and recovering boats safely at sea (a device now widely used on ships) will go uncredited. God knows the true identity of its inventor; and that, one senses, is enough for Captain Beveridge.

Dominic Brown